By Mike Whitney | 24 October 2007

Is it really fair to blame one man for destroying the US economy?

Probably not. But Alan Greenspan is still tops on our list. After all, Greenspan "presided over the greatest expansion of speculative finance in history, including a trillion-dollar hedge fund industry, bloated Wall Street-firm balance sheets approaching $2 trillion, and a global derivatives market with notional values surpassing an unfathomable $220 trillion." (Henry Liu, "Why the Subprime Bust will Spread," Asia Times) Greenspan is also responsible for slashing the real Fed Funds Rate so that it was negative for 31 months from 2002 to 2005. That decision flooded the housing market with trillions of dollars in low interest credit, creating the largest equity bubble in history. Now that that bubble is crashing, Greenspan has hit the road. He now spends his time leap-frogging from city to city, hawking his revisionist memoirs of how he steered the ship of state through troubled waters while fending off protectionist liberals. Look for it in the Fiction section of your local bookstore.

Still, can we really blame "Maestro" for what appears to have been a spontaneous flurry of "free market" speculation in real estate?

To a large extent, yes. Apart from Greenspan's tacit endorsement of all the dubious loans (subprime, ARMs etc) which flourished during his reign, and despite his brusque rejection of the Fed's role as regulator, the Federal Reserve's own documents ("House Prices and Monetary Policy: A Cross-Country Study") indicate that housing was "specifically targeted," acknowledging that it would serve as "a key channel of monetary policy transmission." This is not even particularly controversial any more. In fact, we can see that this same scam has been used in England, Spain and Ireland— all now suffering the ill effects of massive real estate inflation. If no one else, bankers should fully understand the effects of cheap credit on the economy.

California housing falls off a cliff

We are now beginning to see signs that the so-far "benign" housing bubble deflation is becoming benign no longer. Last week's news from Southern California confirms that home sales have plummeted a whopping 48.5 percent from the previous year. This represents the biggest decline in home sales since the industry began keeping records more than 20 years ago. Sales are at a standstill and builders and homeowners have begun slashing prices in desperation. (See YouTube: "Central California Housing Crash")

The news is only slightly better in the Bay Area where DataQuick reports that "Bay Area home sales plummet amid mortgage woes":

A total of 5,014 new and resale houses and condos were sold in the nine-county Bay Area in September. That was down 31.3 percent from 7,299 in August, and down 40.1 percent from 8,374 for September a year ago. |

40.1 percent year over year. That is the definition of a market collapse.

"Foreclosure activity is at record levels."

September sales figures for the rest of the country are not yet available, but what is taking place in California, is what we anticipated after the subprime credit market "froze over" on August 16. Most people don't understand that markets nearly crashed on that day and that the tremors from that cataclysm changed the way the banks do business. Many of the loans which were available just months ago (subprime, piggyback, ARMs, "no doc," Alt-A, reverse amortization, etc.) are either much harder to get or have been discontinued altogether. Additionally, the banks are no longer able to bundle mortgage loans into securities and sell them to investors. In fact, the future of "securitization" of mortgage debt is very much in doubt now. An article in the Financial Times shows how this process has slowed to a trickle: "Only $9.9 billion of home equity loan securitizations have come to market since July 1— a 95 percent decline from the $200.9 billion in the first half of this year and a roughly 92 percent decrease from the same period last year."

Many potential buyers are now finding that they no longer meet the stricter standards the banks are using to determine credit worthiness. This is especially true for 'jumbo' loans, that is, any home loan that exceeds $417,000. The banks are getting increasing skeptical (some believe many are also hoarding capital to cover bad bets on mortgage-backed derivatives) in determining who is a qualified mortgage applicant. Understandably, this has thrown a wrench in sales figures and slashed the number of September closings in half.

In other words, the credit meltdown on Aug 16 changed the basic dynamics of home mortgage lending. Decreasing demand and mushrooming inventory are only part of a much larger problem; the financing mechanism has completely changed. The banks are increasingly reluctant to lend money. And, when banks don't lend money, bad things happen. The economy will die for lack of credit. Despite the valiant efforts of the Plunge Protection Team in engineering a late-day turnaround of the August rout, the damage is done. Much tighter lending will put additional downward pressure on a housing market that is already in distress, speeding us towards recession. The economic storm clouds are already visible on the horizon.

Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson has finally admitted that the slumping housing market is now the "most significant risk to the economy." Fed chairman Ben Bernanke agrees and adds that he believes that housing would be a "significant drag" on GDP. The troubles at the banks and the news from California have perhaps shaken the confidence of both men. But there's little they can do. Millions of people are "in over their heads" living in homes they clearly can't afford. They'll be forced to move in the next several years. Foreclosures will soar. That isn't likely to be avoided. Also, the industry has a 10-month [[and still growing?: normxxx]] backlog of existing homes that must be reduced before the housing market has any chance of rebounding. That takes time. Construction and construction-related industries will especially suffer substantial losses.

The problems facing the banks are much more serious than anyone cares to openly discuss. The large banks are overextended and undercapitalized. The CBersd have provided more than $400 billion in cash injections since the August meltdown, bu the troubles persist. The Treasury Dept. has joined with Citigroup, Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase in an attempt to 'repackage' bad debts and sell them to wary investors via a "super conduit" mega fund [[still, there doesn't seem to be enough lipstick to make this 'pig' saleable: normxxx]]. Desperation is palpable and this latest maneuver only adds to rising market jitters.

There's a still a strong belief that the Fed chief can wave a magic wand and make things better. But that is not the case. Bernanke's decision to cut the Fed's Fund Rate last month did not affect long-term rates and, therefore, did not make it cheaper to buy (or refinance) a home. The rate-cut was really just a gift to tide the banks over that are currently buried under about $400 billion in mortgage-backed debt and CDO sludge that they can't offload without taking a severe 'haircut'. The increase in liquidity hasn't made these toxic securities any more saleable or solvent. Nor has it increased the banks' willingness to provide new home financing to mortgage applicants. That process has slowed to a crawl. All the Fed has done is to buy more time for the banks while they try to wriggle out of their enormous but so far just 'potential' (i.e., off-books) losses.

The banks serve as the principal conduit for the transferal of credit to consumers. That conduit has turned into a chokepoint due to defaults in the mortgage industry and the banks own overhanging debt-load. The Fed cannot get money to the people who need it and who can keep the economy growing. This is a structural problem and it cannot be resolved simply by cutting rates.

We've already begun to see signs of a slowdown in consumer spending at Target, Lowe's and Wal-Mart. If that deceleration continues, the economy will slip quickly into recession.

American consumers have withdrawn over $9 trillion from their home equity in the last seven years. That spending-spree has kept the economy whirring along at a healthy clip. Now that housing prices have stopped going up and, in many cases, gone down, that easy money is no longer available— setting the stage for shrinking economic growth, slower home sales, and declining all-around demand. Deflation is the Fed's worst nightmare and will be fought with every weapon in their arsenal.

Regrettably, Bernanke does not have the tools to fix this problem and he is likely to destroy the currency if he keeps cutting rates— just about the only effective tool available to him. The recent cuts have already sent oil and gold to new highs while the dollar continues to nosedive. (The euro stands at $1.43 per dollar, up over 63 percent since Bush took office.) The weak dollar and the persistent credit problems in the markets, has sent foreign investors scampering for the exits. August was the biggest month on record for the withdrawal of foreign capital from US securities and Treasuries— $163 billion in capital flight. (Japan and China led the way.) Confidence in US markets, leadership and integrity have never been lower. Investors are voting with their feet. They've had enough.

At the present pace, the US will not be able to maintain its $800 billion current account deficit, which means that prices will rise, the dollar will fall still further, and consumer spending will dry up. No amount of financial tinkering at the Federal Reserve will make a bit of difference. Barring a dramatic change in economic policy— which seems unlikely— we appear to be quickly moving towards a system-wide, market-busting, breakdown [[say, about 2009?: normxxx]].

The mess that Greenspan made

The ruinous effects of Greenspan's housing bubble can't be fully appreciated unless one spends a bit of time studying some of the charts and graphs that are now available. These graphs are the best way to dispel any lingering suspicion that the housing bubble may be just another conspiracy theory. It's not, and these links should provide ample evidence to the contrary.

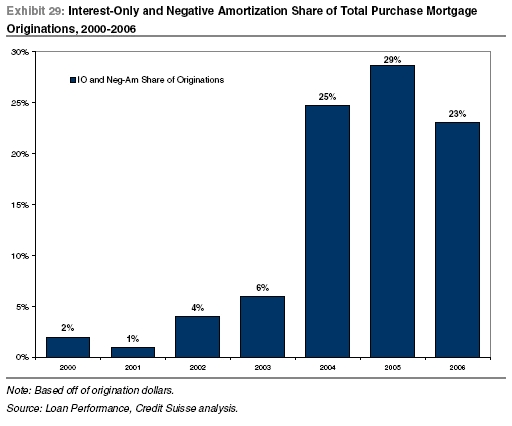

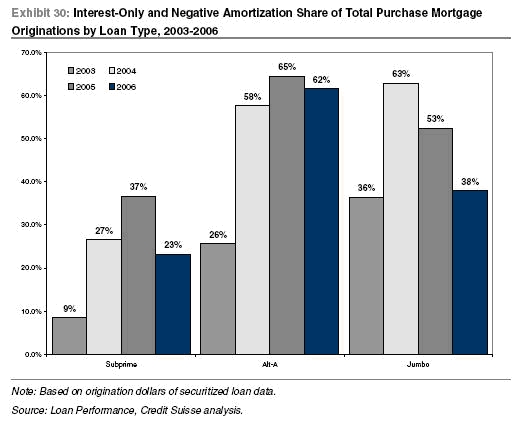

The first graph is the ARM (adjustable rate mortgages) reset schedule, totaling hundreds of billions of dollars in the next two years. The next two are the interest only and negative amortization share of total mortgage purchase originations for 2000 - 2006. Keep in mind, when studying the ARM reset graph, that a "study commissioned by the AFL-CIO shows that nearly half of homeowners with ARMs don't know how their loans will adjust, and three-quarters don't know how much their payments will increase if the loan does reset. 73 percent of homeowners with ARM's don't even know how much their monthly payment will increase the next time the rate goes up." (Calculated Risk)

The unwinding of the housing bubble is now beginning to show up in other areas of the economy. Credit card debt has skyrocketed to 17 percent annually now that homeowners are no longer able to tap into their vanishing home equity. Americans already owe over $500 billion on their credit cards. Now that debt is increasing faster than [discretionary?] retail sales, which suggests that many people are so overextended they are using their cards for basic necessities and medical expenses. Industry analysts now expect an unprecedented wave of credit card defaults in the next six to 12 months. Unfortunately, for the tapped-out consumer, the credit card represents his last access to any kind of additional funds.

We can also expect the downturn in housing to swell the unemployment lines. Oddly enough, while home sales have declined 40 percent from their peak in 2005, construction-related employment has only slipped 5 percent. That is really astonishing [[The loss of jobs in the construction and finance industries lag (also, illegal aliens do not show up in the stats); most of the people in the 'sales' and many in the 'finance' end ('brokers' and such) of the housing boom were 'independent contractors' and, as such, paid no unemployment insurance nor are entitled to receive it now, so do not show up in the 'unemployment' statistics: normxxx]]. It could be that the BLS is hiding the numbers using its Birth-Death model. But we know that construction has accounted for two out of every five new jobs in the US for the last six years, so we are sure to see a significant rise in unemployment as the bubble continues to deflate. The financial and mortgage industries have already experienced significant layoffs.

Similarly, we can expect to see substantial correction in home prices. Housing price declines typically lag six months after a sales peak as inventory rises. So far, prices have dropped a mere 3.5 percent, whereas inventory is at historic highs and sales have decreased 40 percent. It is impossible to know how low prices will go (some experts like Robert Schiller predict 50 percent cuts in the hotter markets), but the downward pressure on housing prices is bound to be enormous [[builders have already cut prices on some of their newest homes up to 35%, with the occasional 50% 'fire sale': normxxx]]. Growing unemployment, zero percent personal savings, a once more flattening salary growth, rising foreclosures, severely rising inflation of key items (medical expenses, education, food, energy), and the prevailing mood of gloominess suggest that the impending fall in home prices will be relentless. (A recent poll showed that a majority of Americans believe we are already in a recession)

Deflationary downward spiral

There is a debate raging on the econo-blogs about whether the country is headed towards a hyperinflationary or deflationary cycle. The argument for hyperinflation is compelling since the Fed has already shown that it is prepared to savage the dollar in order to keep the economy running. As a result, we've seen inflation heating up at a pace not seen in over a decade, despite the government's doctored figures. In September, gasoline costs rose 4 percent, heating oil soared 9 percent, food jumped 5 percent, and dairy products lurched ahead 7.5 percent. Everything is up except the greenback, which appears to be in its death throes.

As American consumers are increasingly forced to accept that they have maxed-out all of their readily available lines of credit, they will have to curtail their spending and live within their means. That means less growth or no growth, a continuing decline in housing, and (perhaps) a sharp fall in equities prices. These are all the harbingers of deflation.

Treasury Secretary Paulson's new "Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit," (M-LEC)— which may allow the investment banks to postpone reporting their losses— is particularly ominous in this regard, since it was the Japanese banks' unwillingness to write-off their bad debts which extended their deflationary recession for 15 years. Can the same thing happen here?

Probably. An interesting exchange took place last month between the widely respected economic blogger, Mike Shedlock ("Mish's Global Economic Trend Analysis") and economist Paul L. Kasriel. [[LINK FIXED:normxxx]] The interview provides details of the Japanese crisis which offer some striking similarities to our present predicament. (A more recent note by Paul K. on his current thinking can be read here.) I have transcribed an extended portion of that discussion:

Banks are an important transmission mechanism between the central bank and the private economy. If the banks are unable or unwilling to extend the cheap credit being offered to them by the central bank, then the economy grows very slowly, if at all. This happened in the U.S. during the early 1930s. U.S. banks currently hold record amounts of mortgage-related assets on their books. If the housing market were to go into a deep recession resulting in massive mortgage defaults, the U.S. banking system could sustain huge losses similar to what the Japanese banks experienced in the 1990s. If this were to occur, the Fed could cut interest rates to zero but it would have little positive effect on economic activity or inflation. Short of the Fed depositing newly-created money directly into private sector accounts, I suspect that a deflation would occur under these circumstances. Again, crippled banking systems tend to bring on deflations. And crippled banking systems seem to result from the bursting of asset bubbles because of the sharp decline in the value of the collateral backing bank loans. Mish: What if Bernanke cuts interest rates to 1 percent? Kasriel: In a sustained housing bust that causes banks to take a big hit to their capital it simply will not matter. This is essentially what happened recently in Japan and also in the US during the great depression. Mish: Can you elaborate? Kasriel: Most people are not aware of actions the Fed took during the Great Depression. Bernanke claims that the Fed did not act strongly enough during the Great Depression. This is simply not true. The Fed slashed interest rates and injected huge sums of base money but it did no good. More recently, Japan did the same thing. It also did no good. If default rates get high enough, banks will simply be unwilling to lend which will severely limit money and credit creation. Mish: How does inflation start and end? Kasriel: Inflation starts with expansion of money and credit. Inflation ends when the central bank is no longer able or willing to extend credit and/or when consumers and businesses are no longer willing to borrow because further expansion and /or speculation no longer makes any economic sense. Mish: So when does it all end? Kasriel: That is extremely difficult to project. If the current housing recession were to turn into a housing depression, leading to massive mortgage defaults, it could end. Alternatively, if there were a run on the dollar in the foreign exchange market, price inflation could spike up and the Fed would have no choice but to raise interest rates aggressively. Given the record leverage in the U.S. economy, the rise in interest rates would prompt large-scale bankruptcies. These are the two "checkmate" scenarios that come to mind. |

Well put. Thank you, Mish.

Normxxx

______________

The contents of any third-party letters/reports above do not necessarily reflect the opinions or viewpoint of normxxx. They are provided for informational/educational purposes only.

The content of any message or post by normxxx anywhere on this site is not to be construed as constituting market or investment advice. Such is intended for educational purposes only. Individuals should always consult with their own advisors for specific investment advice.

No comments:

Post a Comment