Or, a short primer on money and banking

By Gary North | 27 September 2007

In my previous article, "How Bernanke Snookered Us All," I made the case that during a one-month period, mid-August to mid-September, 2007, the Federal Reserve System deflated the adjusted monetary base. As with Austrian economists generally, I define "inflation" as "an increase of the money supply." [[But see also click.: normxxx]] I define "deflation" as "a decrease in the money supply." [[But see also click.: normxxx]] The adjusted monetary base (AMB) [[See also click.: normxxx]] is the only monetary aggregate that the FED controls directly. I referred readers to the chart and table provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis which tracks this statistic. I do so again.

I said that this decrease in the monetary base was significant because this was during a period in which the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve System was actively intervening in the market known as the Federal Funds Rate, i.e., overnight loans between banks, from banks to other banks. This rate had been exceeding the target rate of 5.25% for over two months. The FED normally intervened once a day to bring this rate back to about 5.25%. I offered a link to a page where anyone may see the daily rate in the FedFunds market: high, actual, and the FOMC's target rate. Here it is.

So far, we know two facts: (1) during the month leading up to the September 18 announcement by the FED of a reduction in the target rate for overnight bank loans to 4.75%, the FOMC was reducing the one monetary aggregate that it controls directly; (2) the FOMC was actively intervening daily to reduce the FedFunds rate to 5.25%[!?!]

- [ Normxxx Here: But see reference below. ]

My conclusion: the FED was buying repos from the banking system (inflationary— more money in circulation) while selling other assets (deflationary— less money in circulation). The FOMC sold more assets than it bought during this one-month period, which is the only way the adjusted monetary base could fall.

Are you with me so far?

I could be wrong about the FED's buy-and-sell techniques of this process. I am always open to suggestions. If someone can show me from the statistics how the adjusted monetary base could fall during a period in which the FOMC was actively intervening to push the interday FedFunds rate back to 5.25%, I want to hear it. I will certainly consider it. But I do not see how I can be wrong about the overall effect of this process: more FOMC sales of assets than purchases.

The adjusted monetary base fell. If the FOMC [[had: normxxx]] increased its [net] purchases of assets in this period, this [[would: normxxx]] indicates that the FOMC has lost control over the monetary base. [[[Because] : normxxx]]The base went down, contrary to the action that traditional central bank theory says must raise it: net purchases of assets. If the base fell while net monetary base assets (Federal Reserve credit) increased, this surely calls for an explanation. I am open to suggestions.

There is a second question: "Can the FOMC continue to do this, i.e., lower the adjusted monetary base while also keeping the Fedfunds rate to 4.75?" My guess is that it cannot— not for long, anyway. But that is a guess. The FOMC did it for a month.

I made this comment with respect to long-term FOMC policy:

- The table at the bottom of the chart provides the important numbers: the rate of increase from various dates until now. From mid-September, 2006, to mid-September, 2007, the increase was 1.8% per annum. This is what it has been ever since Bernanke took over on February 1, 2006.

An increase of 1.8% is tight money policy by previous FED standards [[any time the rate of increase of AMB is below the rate of inflation, money policy is tight: normxxx]]. I have been hammering on this point for a year. The FED has dramatically reduced the rate of monetary inflation.

I do not see how I could have been more clear. I did NOT say that the FOMC is deflating long-term. It is disinflating, compared to what the FOMC had done under Greenspan.

Fractional Reserves

One criticism I received from more than one source was this: the banking system can create credit, which is money, independent of the Federal Reserve System's monetary base.

At this point, the critics are breaking with what money and banking textbook authors have written about central banking for a century. Let me briefly review the argument of all economists— Austrian, Keynesian, Chicago School, and supply-side.

The central bank creates money when it purchases assets— any assets— for its account. It spends this new money into circulation when it buys an asset. This new money is deposited automatically in the asset-seller's account in a commercial bank. The fractional reserve process then takes over. This new money is used by the bank to make loans. The banks of the borrowers do the same, setting aside the required non-interest-bearing reserves with the FED. [[That is, the borrowers deposit the 'new' loan money into their own banks, and then their banks can lend out this money, less a small amount set asided as a required reserve, and so on, almost ad infinitum— this is known as "fractional reserve banking": normxxx]] When the process [eventually] ceases, the [[sum of all of the: normxxx]] reserves deposited with the FED [must] equal the initial purchase of assets by the FED. This is the standard textbook account.

Let us get this clear: the basis of all new credit created by the commercial banking system is the new money issued by the central bank.

In textbooks on money and banking, this process is described by the use of a conceptual tool called a T-account. Step by step, the author shows how the initial deposit of a check in a bank leads to the creation of new credit. The FED makes this initial deposit.

The best textbook I have seen on this process was written by Murray Rothbard: The Mystery of Banking (1983). You can download it for free here.

There are newsletter writers who argue that the banking system as a whole can create credit independently of an addition of Federal Reserve fiat money, which is often called high-powered money. I am surely willing to consider such an argument. What I need is evidence. I need to be shown how the commercial banking system as a whole can issue credit in a form that is not regulated by the central bank's legal reserve ratio.

As evidence, I would like a reference to some position paper issued by the FED which explains this. Also acceptable: a reference to a textbook or an academic journal that shows how the traditional textbook discussion of reserve requirements is incorrect.

Anyone who argues that fractional reserve banks can create credit that is not under the law regarding reserve requirements is making a very remarkable argument. For one thing, he is making it difficult to understand why the federal funds loan market even exists. The FedFunds market is universally recognized as a market for a bank that has temporarily exceeded its reserve requirement for the creation of new loans (credit) to meet this requirement by borrowing from another bank. Here is the description provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Fed funds are unsecured loans of reserve balances at Federal Reserve Banks between depository institutions. Banks keep reserve balances at the Federal Reserve Banks to meet their reserve requirements and to clear financial transactions. Transactions in the fed funds market enable depository institutions with reserve balances in excess of reserve requirements to lend them, or "sell" as it is called by market participants, to institutions with reserve deficiencies. Fed funds transactions neither increase nor decrease total bank reserves. Instead, they redistribute bank reserves and enable otherwise idle funds to yield a return. Technical details on fed funds are described in Regulation D.

Are bankers irrational? No. Are they in the habit of giving away money to other bankers? No. Then why does any bank borrow overnight money in the FedFunds market? The universal answer is: "To meet its reserve requirements for the day." If this answer is incorrect, then he who argues that the banking system can issue more credit than is allowed by the FED needs to show why this traditional argument is incorrect.

If the monetary base does not set the limit for bank credit, then he who argues this way needs to show why the entire academic field of money and banking has been wrong for over a century. He has to show that Murray Rothbard ignored something fundamental when he wrote The Mystery of Banking and his earlier book, Because, if the private commercial banks can create credit— money— independent of the government-licensed monopoly of the national central bank, then government is not the culprit that has destroyed our money; commercial banks are doing this all on their own.

You can download Rothbard's other book, which I regard as the best introduction to monetary theory despite being short, free of charge.

There are lots of things about money and banking that I do not understand. But I always thought I understood this: a central bank controls a nation's money supply by controlling (1) the reserve ratio and (2) the monetary base. Anyone who argues that commercial banks can and do issue credit independently of these two restraints is arguing that traditional monetary theory is incorrect. Such an argument requires considerable evidence.

Again, I am not saying that such evidence does not exist. I am saying that, so far, I have not seen anyone present it, especially those analysts who say that the commercial banking system, as a system, can do this any time it wants.

The bankers always want to maximize their revenues. They do this by creating credit, which is based on their banks' deposits. They do this at all times. They do not leave a penny on the books in a deposit that is not lent out at all times. Bank credit is always maximized.

Remember this: bank credit is money. Whatever a bank lends is money. This money buys things, which is why borrowers borrow it. They repay in money. Bankers want to be repaid in money. Credit is issued in the form of entries into borrowers' accounts. There is no bank credit that is not in the form of a deposit in a bank account. So, if anyone is increasing the supply of credit, this credit is in the form of an entry into a bank account. Bank accounts are regulated by the FED reserve requirements.

What we need to understand from those analysts who argue that the monetary base does not set monetary policy for the nation is exactly how the commercial banking system in the aggregate can issue credit independently of the FED's monetary base and its reserve requirements (which rarely change).

Is this too much to ask? So, you had better ask it. If someone tells you that the FED has lost control over the monetary system, and that banks can issue credit independently of the FED, ask him to explain why the standard textbook account is wrong, why T-account analysis is wrong, and how on earth Murray Rothbard got it wrong. The person who shows this may even win the Nobel Prize in economics, which is now over a million dollars. It seems like easy money to me for someone who argues that bank credit is independent of deposits in bank accounts.

Why M-3 Was Always Worthless

In my previous report, I wrote this about M-3.

- I don't think my message has penetrated the thinking of most hard-money contrarians. They keep citing M-3, which was canceled by the FED a year ago, and which was always the most misleading of all monetary statistics. Year after year, the M-3 statistic was four times higher than the CPI. The M-3 statistic was worthless from day one. Anyone who used it to make investments lost most (or all) of his money. I have written a report on this, which provides the evidence: "Monetary Statistics."

The main purpose of following monetary statistics is to estimate what effect this will have on two things: (1) the price level; and, (2) the business cycle. Point #1 raises the question: Which statistics of prices?

The theoretical question of constructing a price index is amazingly complex. The best book on the question of price indexes was written in 1950 by economist Oskar Morgenstern, On the Accuracy of Economic Observations. Morgenstern was one of the few men smart enough to be invited by Ludwig von Mises to attend his private seminars in Austria. There is a good presentation of the implications of this book is posted on the Mises Institute's site.

I use the Median CPI figures— and other figures— to see the trend of past prices. I want to have some sense of how rapidly prices are trending upward. The statistics of the Median CPI go back 40 years. They are posted here (this week, anyway; they constantly change its address, which is very annoying).

I update the link whenever the Cleveland FED updates it. It is always on-line at my free department, "Price Indexes" (U.S.A.), here.

I have subscribers who tell me in no uncertain terms that all consumer price index statistics are fake. My response: as long as they are consistently fake, I can still use them to see the trend of prices. Only when the statisticians change their assumptions do the statistics become useless for assessing past periods that were not updated in terms of the revised assumptions. Even jiggered figures are useful if the statisticians retroactively revise previous figures. I can still see the trend.

Conclusion

I maintain that a nation's central bank controls the nation's money supply. It does so with two tools: (1) the legal reserve requirement, and (2) the purchase (inflationary) or sale (deflationary) of assets in its possession— the monetary base.

If someone says that a central bank does not control the nation's money supply in this way, then he owes it to his readers to explain either: (1) other ways that the central bank controls money; or (2) the ways that the commercial banks escape the controls set by the central bank. Either of these assertions requires textbook or similar evidence: simply saying that the central bank has lost control does not prove that it in fact has lost control.

———————————————————————————————————————

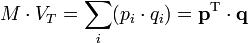

[ Normxxx Here: What most people miss or forget is that there are four parts to the Quantity Theory of Money Equation.

[The mathematically challenged can skip to the text below at "This equation"]

In its modern form, the Quantity Theory builds upon the following definitional relationship.

where

is the total amount of money in circulation on average in an economy during the period, say a year.

is the total amount of money in circulation on average in an economy during the period, say a year. is the transactions' velocity of money, that is the average frequency across all transactions with which a unit of money is spent. It is derived from the other values in the equation.

is the transactions' velocity of money, that is the average frequency across all transactions with which a unit of money is spent. It is derived from the other values in the equation. and

and  are the price and quantity of the i-th transaction.

are the price and quantity of the i-th transaction. is a vector of the

is a vector of the  .

. is a vector of the

is a vector of the  .

.Or, more simply:

where

V is the velocity of money in final expenditures.

Q is an index of the real value of final expenditures.

This equation, like the previous one, holds because V is constructed to make the two sides equal, although it is intended to represent the number of times a fixed amount of money changes hands in a given period (say, a year).

As an example, M might represent currency plus checking and savings-account money held by the public, Q real output with P the corresponding price level, and PQ the nominal (money) value of output. In one empirical formulation, velocity was defined as "the ratio of net national product in current prices to the money stock."

But, we ignore V at our peril, since this factor is as important as the quantity of money for inflation, and is crucial to understanding hyperinflation. Just because it is constructed by economists from the other elements of the equation doesn't mean it is not a real variable in the economy— it is calculated because there are (conveniently?) no direct means of measuring it. And no known way to control it independently of money supply.

To better understand V and why it changes as it does, there is no better article than Paul Tustain's "Hyperinflation: Creating Repulsive Money."

Next, there is the factor of "virtual" money. "Virtual" money (aka "paper" money, but not to be confused with Federal Reserve Notes) is what a thing (say, a stock or a derivative or a house) is measured in. It is not "real" because it does not represent any intrinsic value of the thing— it is usually set by so-called "market" transactions (i.e., recent purchases and sales of like things). In this sense, we can see that, e.g., gold has no 'intrinsic' value either— only a "market" value. We can at best argue that gold has been more stable than the dollar in price (what other things one can obtain/"buy" with it) over a large number of years. But if all (or even most) of the owners of gold decided to sell it at the same time, one fine day, its price would rapidly diminish towards zero, lacking an infinitely "liquid" market.

Thus, the amount of virtual money represented by all of the things of value (not necessarily only goods) in an economy, may be many, many times the (adjusted) monetary base (ABM). Virtual money is constantly being created and destroyed. When a stock goes up by one dollar, the total virtual money created is the stock's number of shares times the one dollar; and conversely, if it goes down, a like amount of virtual money can be said to be destroyed. This is true of housing; if the value of the most recent sales of like houses in my neighborhood goes down by $50,000, then I assume I have lost $50,000. That is because the instant I purchased my home, its value became virtual (it was real only at the point of transaction). What happened to the vanishing $50,000? It is held by the last seller of my house (assuming my house is now worth $50,000 less than when I purchased it)— or, if it is only $50,000 less than the last time I estimated its value, it never existed as real money in the system anyway, and so vanishes without a trace, like most dreams— all I can look forward to is realizing the virtual value of my house at any given time.

The Fed has precious little control of V, and absolutely no control of the virtual money supply.

But does the virtual money supply influence prices and inflation/deflation? Yes, of course, but being an imaginary quantity it can do so only indirectly through its influence on the psychology of economic person (aka, 'economic man').

First, it is obvious that having a virtual price for a thing allows one to transact in terms of an increase or decrease from that relative virtual price, which is far easier than trying to establish a value where none is known. So, it greatly diminishes price fluctuations and minimizes the possibility of 'wild bargains' and equally wild 'paper' losses (what one could have gotten for the thing less what one actually got). In the 'olden days', the value of a thing was generally somewhere around the minimum price a seller was prepared to part with it for, and the maximum price that a purchaser felt the thing was worth to him (or her). Such transactions often consumed the greater part of a day (or even several days for 'big ticket' items).

Second, virtual money value is the crucial factor in the "wealth effect"— how "rich" one tends to feel. And the "wealth effect" is a crucial factor in our propensity to spend (or save)— V, again. Moreover, since the wealth effect is psychological, it partly depends on the type of things one has and our personal or learned experience in converting such things into money. For most people, up until recently, a $500,000 house seemed a good bit more 'real' than an equal amount of stock, and probably contributed more to their feelings of wealth. Too, one can easily see how the current generation is far readier to equate their virtual worth with real money— as opposed to the post Great Depression generation, for example.

Lastly, There Is The Magic Of Derivatives, Or, How To Make Money Out Of Thin Air

We all live in the small town of X, Tomm, Dikk, Harrry, and I. Everybody knows that our word is as good as any bond. So, on Tuesday, thinking I might go to Big City, I borrow $10 from Tomm, giving him an IOU in exchange. On Wednesday, Dikk borrows the $10 from me (obviously, before I can spend it) and gives me an IOU for it. Then Harrry borrows the $10 from Dikk in exchange for an IOU. Now there are $30 of IOUs and one $10 bill in circulation— $40 where before there had only been the one $10 bill. Tomm, Dikk, Harrry, and I are not banks and pay no heed to the CB, much less pay any "fractional reserves," but we have just upped our local money supply by 300%!

Now this is just penney ante and is not likely to shake up the financial structure much. But when banks (and others) 'issue' derivatives, promising to pay money based on the outcome of some future event (like a mortgage being paid back)— but not strictly money nor a loan, and so completely outside of the Federal Reserve or any CB System, it explains how the world 'money supply' can be increased by over 40 times (not three times as in our penney ante example). In most cases, these derivatives can be used just like money (or, at least until the s--- hits the fan).

Tomm, Dikk, Harrry, and I can use those IOUs freely in lieu of cash, as long as we stay in X (where everyone knows us and is willing to take the IOUs). But, if I get run over by a horse some day, and die intestate, Tomm may be a long time in getting his $10 back, since neither Dikk nor Harrry owe him anything; although Dikk owes $10 to my estate, and Tomm can file a claim against my estate, assuming there is anything left after burial expenses.

———————————————————————————————————————

Now all I have left to do is tie this all together, but I'll leave that for another day. normxxx

———————————————————————————————————————

A postscript from Hussman's comments (see Reference): On Thursday, September 27th, the Federal Reserve entered into $6 billion in 14 day repos and $20 billion in 7 day repos. It also rolled over two small, shorter-term repos from earlier in the week that will roll over again on Monday— probably at least $10 billion, with a weekly total of about $30 billion by Thursday October 4th, to extend other repos that come due at that time. As of last week, the total amount of Fed repurchases outstanding is $44.75 billion. This is close to the total quantity of reserves in the U.S. banking system (which includes these repo proceeds). Meanwhile, total borrowings of depository institutions from the Fed— the much vaunted "liquidity" lent by the Fed at the Discount Rate— dropped from $2.4 billion to just $306 million last week, which is about the norm of recent years.

In short, next to nothing is actually lent through the discount window. Meanwhile, the Fed's open market operations are not injections of new liquidity, but a continuous rollover that finances a stable level of reserves, at a level that is negligible in relation to $6.3 trillion in total bank loans. If investors want to believe the superstition that Fed actions have anything but psychological effect, they should at least be prepared to demonstrate a specific mechanism by which observable FOMC operations exert that effect. It certainly is not through meaningful "injections of liquidity" into the banking system.

REFERENCE:

To See How Little The Fed Does Actually Control, See Hussman: Show Me The Money!

Remarkably, while arguing different aspects of the same facts and coming to somewhat different conclusions, Gary North and John Hussman are NOT in any dispute on the fundamental facts or issues, nor could they be.

Normxxx

______________

The contents of any third-party letters/reports above do not necessarily reflect the opinions or viewpoint of normxxx. They are provided for informational/educational purposes only.

The content of any message or post by normxxx anywhere on this site is not to be construed as constituting market or investment advice. Such is intended for educational purposes only. Individuals should always consult with their own advisors for specific investment advice.

No comments:

Post a Comment